.

AJ — The Life Of America’s Greatest Race Car Driver Part II

.

AJ Foyt — The Life Of America’s Greatest Race Car Driver, Excerpts from the Book, Part II

.

.

From the book The Life of America’s Greatest Race Car Driver written by AJ Foyt with William Neely copyright 1983 published by Warner Books Inc, NY, NY Chapter 6 “The Good Years” pages 172 – 180.

.

.

.

Writers are constantly writing about sportsmanship in racing. They say I’m the worst loser who ever lived. They’re probably right. But I didn’t start in the sport to lose. And I didn’t become the first four-time USAC champion by being a loser. I did it by being a winner. And I went on to win more championships. None of them by losing.

Racing is not a professional for sportsman. I mean, there are guys who run over you to win. If they try, you have to run them off the track for the run you off. I drive hard, but I drive clean. And I can give as much as I can take. More, in fact.

Cheating doesn’t fall into the same category. I think any race driver worth his salt will cheat if he can. And you know, I think “cheating” is a poor choice of words. We just bend the rules as far as they will possibly bend. If there’s a loophole, we will sneak through it. Al Unser said, “A.J. showed us all how. He wrote the book on bending rules and running hard. The guys in racing are tough, but Foyt is tougher. I mean, he won’t hurt you to win, but he will risk hurting himself. We just practice what A.J. preaches.”

I think that says it pretty well.

NASCAR drivers pride themselves on their “cheating.” They think they invented it. They didn’t, of course, but they sure worked it out to an art. It was more of a necessity for them than it was at Indianapolis. Indy cars are race cars from the first bolt to the last, but stock cars, actually start out as true stock cars, right-off-the-showroom-floor passenger cars.

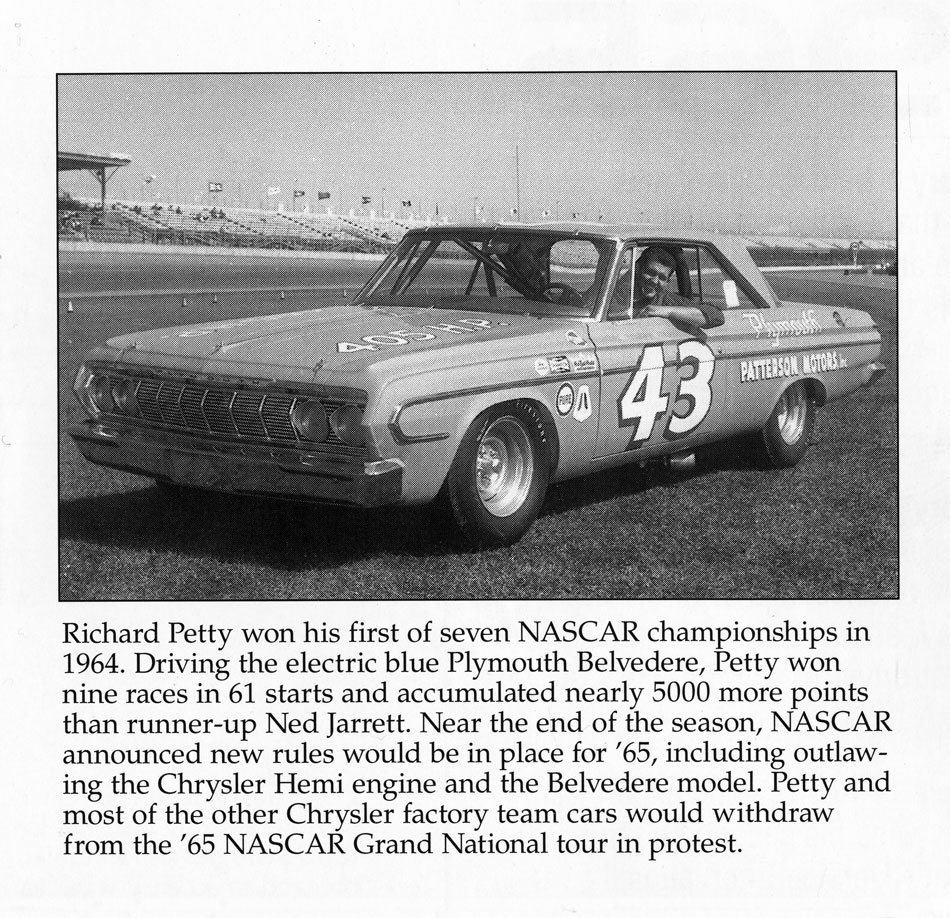

The first NASCAR race was in something like 1948, and a bunch of guys, including Richard Petty’s father, Lee, got together at a dirt track in Charlotte and raced whatever cars they could come up with. The run-what-you-brung days. The rules were that the cars had to be late model and had to be completely stock, which is about as dangerous for racing is anything could be.

Even today’s cars–hell, particularly today’s cars (1983) — would be totally unsafe on a racetrack. The shock absorbers and the springs are designed to give a good, soft ride, and that’s not what you want for racing. You need a stiff suspension so the car won’t lean and bounce all over the racetrack. And the unit-body frames, or whatever the particular manufacturer wants to call them, aren’t strong enough to withstand the average 50-mile-an-hour crash, let alone a high-speed crash.

But those first stock cars were just what the name said. Lee Petty had borrowed a friend’s Buick Roadmaster for the first race, because it was heavy and fairly fast for a street machine. He was leading the race, but the car got to bouncing so bad that he flipped it. Totaled it. After the race, they washed off the number and towed it out to the highway and pushed it in a ditch, so the guy who owned the car could collect on his insurance.

It was right after the first race that they started to cheat. First came stiffer shocks. When everybody started using them, NASCAR threw up its hands and made them legal. Then other suspension parts. Legal again. Then wheels and exhaust systems. And on and on until the stock car was a fast, safe machine.

This is were I came in.

The track record at Indy was 158 miles an hour. In 1965 Darel Dieringer sat on the pole at Daytona with the speed of 172. Man, that’s motoring!

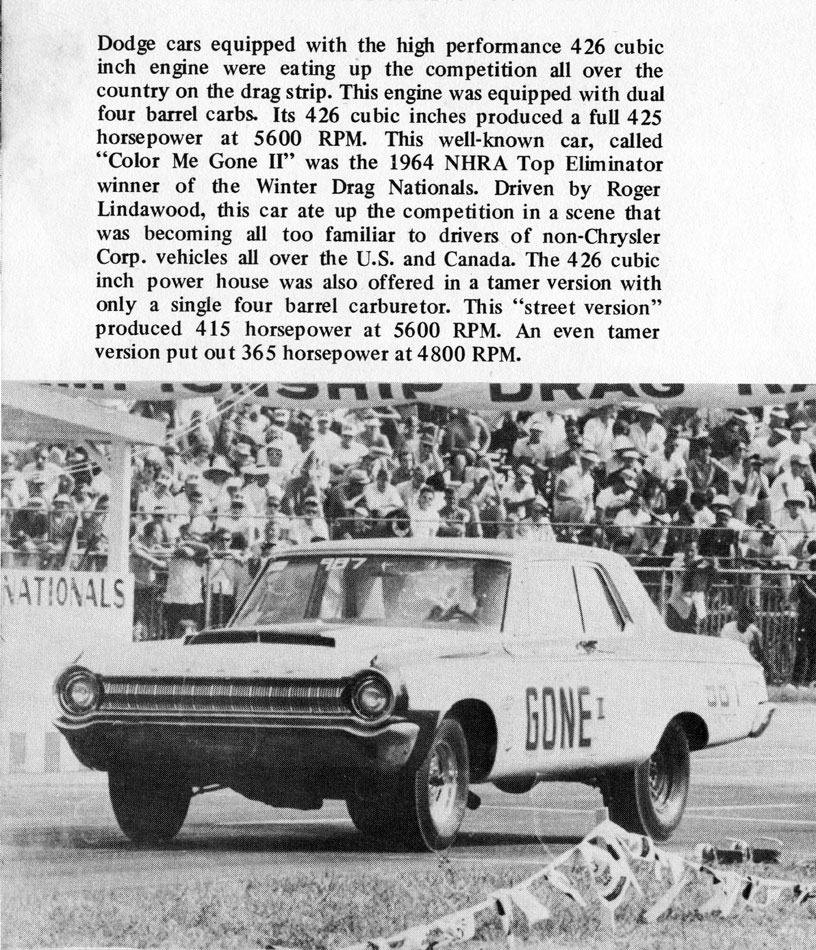

Dieringer’s Mercury was the only Ford product that had a chance. I had been racing Fords, but I switched just before I went to Daytona. The Dodge was a faster race car.

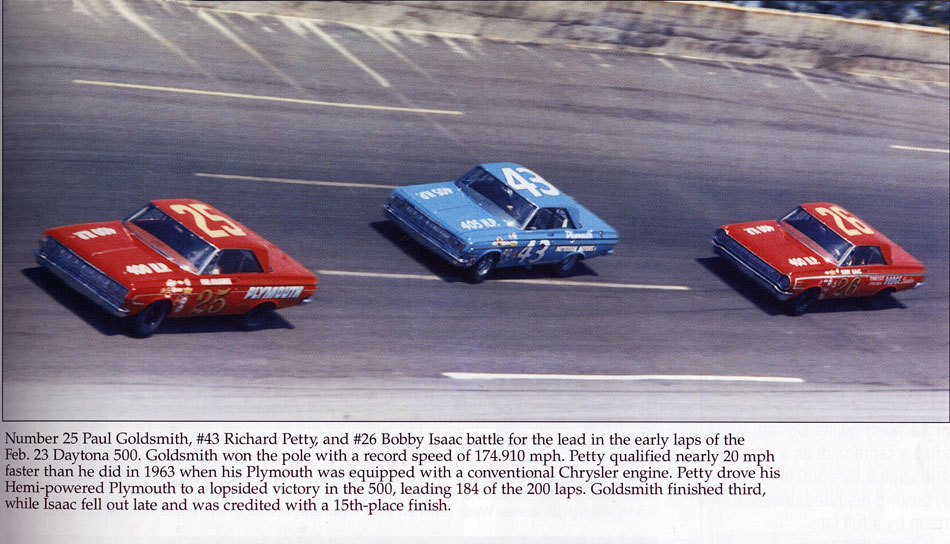

Dieringer got an early lead, but he couldn’t hold off the Mopars. Richard Petty took over at about the fortieth lap, and Bobby Isaac (in his Race Hemi Dodge) and I were right behind him. I had a little trouble getting past Richard the first time, because he drives the same kind of groove I do — up high. But they do a thing in NASCAR called “drafting,” and that helped me.

Drafting is simple. You just pull right up behind a guy at full speed and you follow him. And I mean right up behind, a few inches away from his rear bumper. What it does is stretch out the air foil that flows over the car at high-speed. Instead of the two separate foils it makes one long one, which is more streamlined. Both cars go faster and they give better mileage. We did it at Indy some, but it works better on the bigger stock cars. Also, the Daytona track is much better for it, because you hardly have to lift for the turns. The track has a much-higher-banked turns — 31 degrees, compared to 12 degrees at Indy — so you can get on a guy’s bumper and stay there for as long as you want. Then, when you’re ready to break away and try to pass him, you just pull down out of the draft and there’s a sort of slingshot effect from coming out of the partial vacuum you’ve been running in. It’s only a couple of miles an hour, if your car is about as powerful as the one you been following, there’s no way he can keep you back there.

The NASCAR drivers rather be running second, in somebody’s draft. They usually wait until the last turn of the last lap to break the draft, and then they sail right on by to win. Unless, of course, they’re much faster to begin with. Then they’re just like any other race drivers. They pour it on and build up as big a lead as they can.

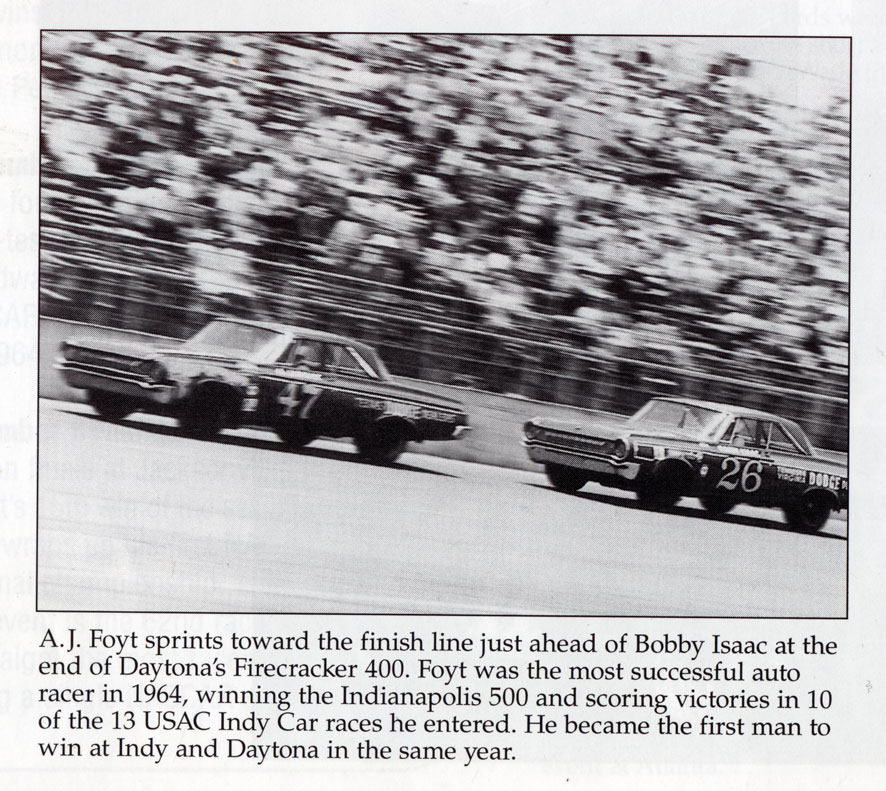

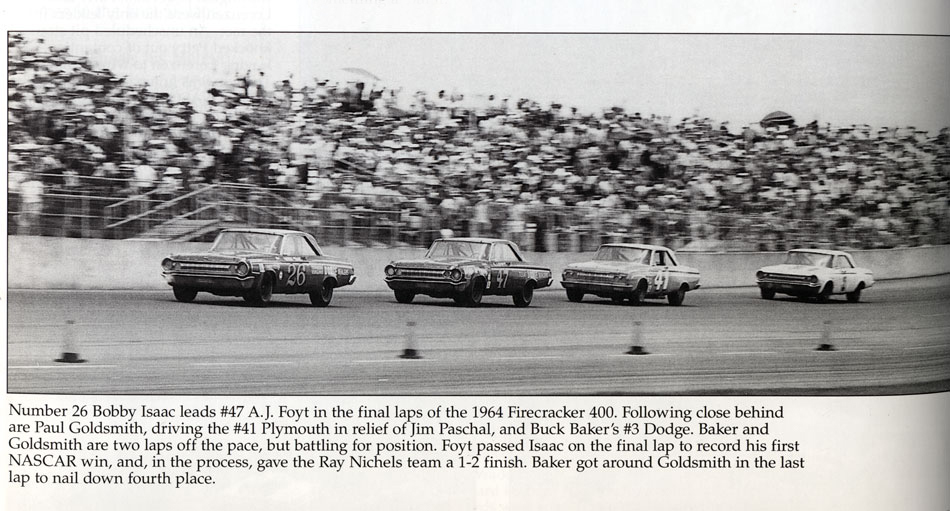

The battle between Isaac and Petty and me went on for lap after lap, until Richard blew his engine. After that it was back and forth, Isaac one lap and me next the next. Until there was only one lap left.

Bobby Isaac was leading and I was right on right on him. Right on him. A couple of times I was so close you couldn’t tell I was tapping his bumper or not. The papers said I was, but I really wasn’t. You try not to hit somebody at 200 miles an hour, and we were running pretty close to that in the straightaways. Isaac expected the slingshot. As I said, there’s not much the front car can do about it. He can’t keep you from passing, so the only thing he can do is use up the best part of the track, so that passing can be so dangerous that you won’t try it.

That’s exactly where Isaac was — right in the middle of the groove. He expected me to pass coming out of Four, but as we came out of Two, headed for the back straightaway, I made my move — earlier than most of them would’ve done it, because they figured that would give the guy a chance to slingshot them out of Four, If I got by in Two, I could hold him off. I knew it.

I drove up high on the bank and started past Isaac on the outside. The force of breaking the draft, plus the speed from coming down off the high bank, shot me right square in the path of Isaac’s front bumper. I felt my car get a little light, like it was on its tiptoes, but I kept my foot to the floor. Isaac had two choices: hit me square in the side, which would have meant crashing both cars at 175 miles an hour, or back off. He drove down low on the apron and backed off.

He had to drive down so low that he had no chance of getting set up to slingshot me in Four. I won Daytona. No driver had ever won both Indianapolis in Daytona before. And I did it in the same year.

It was a six-car Mopar sweep. Ford had used the slogan “Total Performance” the year before, because they had totally dominated racing, so after the Daytona race, Dick Williford , Plymouth’s PR man, passed out badges that read “Total What?” Everybody was wearing them that night at the party at Robinson’s.

At Salem, Indiana, they offered a $1,000 bonus to the first driver who could break the 100-mile-an-hour mark on the half-mile track in a sprint car. Nobody had ever done it. I went out and turned a 100.1 on the first lap.

Next I went to Sebring, Florida, for the twelve-hour sports-car race. Very European. Well, it wouldn’t be the first time I could handle European types. It was a sporty-car crowd, though, and a lot of them said that just because the driver had won Indianapolis and Daytona didn’t for one minute mean that he could come down there and just walk away with everything.

There were a lot of people with tweed on. And sports caps. They brought along fancy baskets of food and they sat around their cars, with little, checkered tablecloth’s on card tables, drinking wine and allowing as how their own kind would win this race.

That was enough right there.

The thing I hated most was the Le Mans start they used in the race. You know, where they line up all the cars on one side of the track and the drivers on the other, and they shoot a gun and you’re supposed to run like hell and jump in your car, start it, and roar off. Shit. That’s stupid.

Everything that could possibly go wrong did. Even with the snooty sporty-car drivers. There were two identical Austin-Healey’s — a team — parked side by side. Both drivers ran over and tried to jump in the same car. Man, they were fighting each other over who’s car it was. They were dead serious. I thought it was as funny as hell.

Another driver jumped in his Ferrari roadster and his entire leg went down through the spokes in the steering wheel. He almost killed myself getting it out. Me? I didn’t get a much better start. For one thing, the special Corvette that John Mecom had built wouldn’t start. The goddamn car wouldn’t start. The field went roaring away without me. The people in tweed snickered. I could see them over by the fence and on the bridge that went over the track. When I finally got it fired up, and nailed it, the car left in a cloud of burning rubber. I had to catch the field, and I had to show a few bastards what a real racer could do.

It was a twisting, turning road course. You have to be right on in the corners. There were tight turns — even a hairpin — and a long straightaway were you could really motor.

By the time I got back to the start/finish line, where the stuck-up sporty-car spectators were, I had passed fifty-one cars. I shrugged as I went past.

I had won the race, hands down, but the car went sour. Still before I dropped out, there were a lot of believers in the crowd.

By the time I got back to Daytona in 1965, I had a following in NASCAR.

I had switched back to Ford, because there had been a lot of changes in the year since the last race. For one thing, Mopar cars were gone. They had won so many races that it got boring — boring to everybody, that is, except the Chrysler people. Ford complained bitterly. They designed their own sophisticated engine and took the plans to Bill France, who ruled NASCAR with an iron hand. France took one look at the engine, which probably cost $20,000 a copy, and said, “Whoa!”

“Listen, if I let you guys use this engine,” he said, “Chrysler will be in here next week with something even more exotic, and it will become the biggest pissing contest in the history of racing.”

They had secret meetings over the whole thing. Very few people knew what was going on, but I got inside information from my friends at Ford. I’ve never before told anybody about my conversations with Ford.

In a desperate attempt to keep the thing from getting any more out of hand, Bill France made the decision. It was based on his fear that NASCAR racing was rapidly approaching the Indianapolis status, where it was so expensive to build a race car that the little guy didn’t have a chance. Mr. Bill France had started Nascar because he wanted the little guy to have a chance. If the engine war got any worse, there would only be a handful of drivers who could afford to put cars on the track that were competitive.

France didn’t allow Ford to bring in their new engine. He outlawed the Chrysler Race Hemi. Chrysler was so pissed off that they pulled out of racing completely, (unfortunately) leaving a lot of their best drivers high and dry. And out of racing.

Lucky I had an official Ford ride.

There really wasn’t much of a race to it. I got out front and built a lead so big that it didn’t look like anybody could catch me. A whole bunch of top Ford executives, including Henry Ford ll, had come down from Detroit to watch their cars get back in the winner’s circle. They leaned back in their expensive seats and counted the laps until the checkered flag, when they could go out and needle the Chrysler people. It was the old Goodyear-Firestone tire thing again – the thing most big companies get into racing for in the first place. They only tell their stockholders that it’s for their image.

They were content in their paddock seats, but I was bored with being so far out front. By then we had two-way radios, and I had been talking to the guys in my crew. The radios are usually reserved for vital information, but at that point I was so far ahead that the only vital information I asked for was the phone number of a really good-looking brunette who was standing at the hurricane fence behind my pit. The stop before, I had asked one of the guys if you gotten her phone number. I mean, that how silly the pit stops were that day.

I radioed again: “Did you guys get the phone number?” “No, we’ll go get it, A.J.,” a guy said. “Now, will you go on and race. We’re tryin’ to take a nap in here”.

They were lounging all over the stacks of tires and generally just soaking up the Florida sunshine. It was time to shake them up. Without saying a word on the radio, I brought the car down low coming out of Three. I was down on the apron and around through Four and coming into the pits before any of them even noticed that I wasn’t out there on the track anymore. All hell broke loose. They fell over the tires and ran into each other trying to get to the pit wall. Up in the paddock seats, the Ford executives dropped their drinks. Although Buddy Baker was way back in second place, he could win. And he was driving a (Chrysler) Plymouth.

I came in sliding to a stop in front of my pit. They were all there, wide-eyed and in a state of panic. They didn’t have any tires ready or any gas. They were just standing there. “What the hells wrong?” they all screamed at the same time.

“Did you get that sweetie’s phone number?” I asked.

“What?” they said. Again all at same time.

“Did you get her phone number?” I asked again.

“We got the goddamn phone number. We got it. Now get the hell out of here.”

I dumped it in first and stood on it. The car got a little sideways as I roared out of the pits. Nobody ever knew why I came in. But up in the stands, the Ford executives collapsed in their seats. I was out in plenty of time to beat Buddy Baker to the checkered flag. But my pit crew was still in a state of shock.

And they didn’t get that phone number at all.

After the race the guys have their annual party at Robinson’s. Of course, they have one the night before the race and the night before that and every night at Daytona. I didn’t go. Bill Neely and I were out racing our rental Fords on the beach. It was a good race. I got him on the ocean side – his mistake – and I guess he figured the beach went straight up to New Jersey or someplace. It doesn’t. At the big turn in the beach – a left-hander – I got it crossed up in front of him and he had to either T-bone me or drive into the ocean. He drove into the ocean. At an indicated 100 miles an hour. You’d be surprised how fast a car stops in water. We left his car and called Avis and told them someone stole his racer.

Meanwhile, back at the party, it got pretty wild. Darel Dieringer left in another rental car, and somewhere between Robinson’s and Ormond Beach, he flipped it, (again) at about 100 miles an hour. A cop was parked beside the road and saw the whole thing. He rushed over, just as Darel was pulling himself out of the driver’s window. “Howdy, Officer,” he slurred.

“Why you’re drunk,” the cop said.

“Of course I’m drunk,” Darel said. “You think I’m a stunt driver or something?”

.

Like what you see and want more? Click for my post A.J. The Life Of America’s Greatest Race Car Driver — Part 1. Enjoy!

.

.

.

.

Excerpt from the book A.J. — The Life of America’s Greatest Race Car Driver written by A.J. Foyt with William Neely copyright 1983, published by Warner Books Inc, NY, NY

Pages 172 – 180.

.